The first stars in the universe may have been much smaller than we thought, new research hints — possibly explaining why it’s so hard to find evidence they ever existed.

According to the new research, the earliest generation of stars had a difficult history. These stars came to be in a violent environment: inside a huge gas cloud whipping with supersonic-speed turbulence at velocities five times the speed of sound (as measured in Earth’s atmosphere).

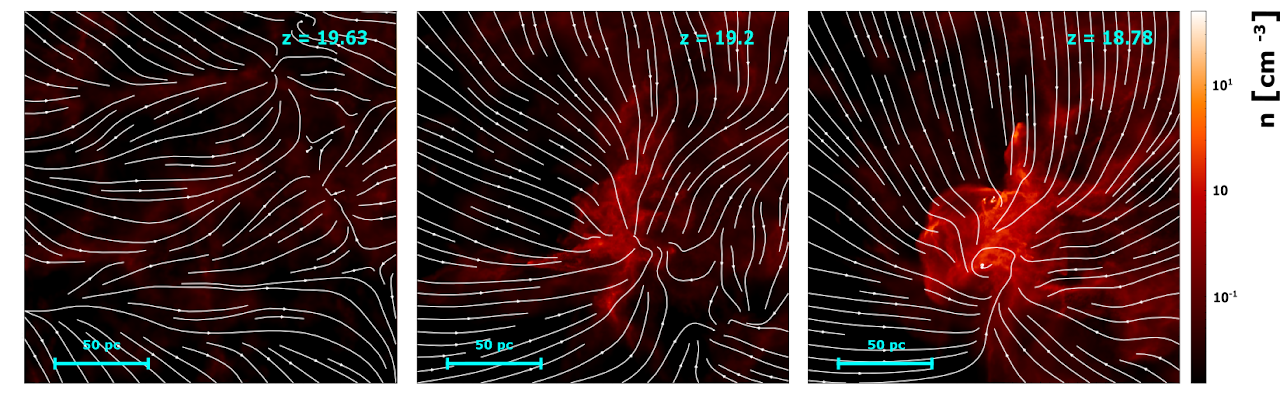

A simulation underpinning the new research also showed gases clustering into lumps and bumps that appeared to herald a coming starbirth. The cloud broke apart, creating pieces from which clusters of stars seemed poised to emerge. One gas cloud eventually settled into the right conditions to form a star eight times the mass of our sun — much smaller than the 100-solar-mass behemoths researchers previously imagined in our early universe.

These findings hint that the first supergiant stars in history may have come to be in stellar networks — not in splendid isolation, as previously thought.

“With the presence of supersonic turbulence, the cloud becomes fragmented into multiple smaller clumps, leading to the formation of several less massive stars instead,” principal researcher Ke-Jung Chen, a research fellow at the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan, told LiveScience by email.

This glimpse of our early history is crucial in learning about the origins of our galaxy, as well as our solar system.

“These first stars played a crucial role in shaping the earliest galaxies, which eventually evolved into systems like our own Milky Way,” Chen wrote. With this new model in hand, he added, fresh observations can bring the research further, studying starbirth and galaxy formation using both computer models and NASA’s powerful James Webb Space Telescope.

Simulating the universe

Researchers generated their fresh understanding of early stars using the Gizmo simulation code, which is used to study astronomical phenomena ranging from black holes to magnetic fields, and a project called IllustrisTNG that has previously been shown to accurately replicate galaxy formation. Their goal was to study the conditions in our cosmos a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago.

Related: Scientists just recreated the universe’s first ever molecules — and the results challenge our understanding of the early cosmos

Given the sheer scale of the universe, the simulation focused on a single area: a dense structure, roughly 10 million times the mass of our sun, called a dark matter minihalo. (Dark matter makes up most of the stuff of our universe, but doesn’t interact with light, and cannot be sensed by telescopes. We can, however, infer the presence of dark matter through its gravitational effect on other objects.)

The researchers examined how gas particles were moving in relatively small regions of space inside the halo, each region measuring roughly three light-years across. Simulations showed the dark matter minihalo attracts gas through sheer gravity, and by doing so, generates both supersonic-speed turbulence and gas cloud clumping. Violence was therefore a part of creating early stars.

This traumatic environment created another side effect: there were fewer huge, early stars than we previously imagined. Previous research had suggested we could have had early stars of more than 100 solar masses each. Eventually, these old stars would have exploded as supernovas, leaving behind traceable remnants that newer stars would incorporate as they grew.

Newer stars, however, do not show any chemical signatures of giant elders inside them — showing that a first generation of enormous stars may have been rare indeed.

Chen’s team isn’t done yet. They are now using the dark matter halos to see how supersonic turbulence worked more generally in the early universe, especially as the first stars came to light in an era more than 13 billion years ago, called “the cosmic dawn.”

“This paper is part of a collaborative effort aimed at understanding the cosmic dawn through investigating the formation and evolution of the first stars,” Chen said.

The next set of simulations may also include magnetic fields, he added. We can see in galaxies today that supersonic turbulence boosts magnetic fields and influences star formation; it may very well be that magnetism was just as crucial to star formation in the early universe.

Chen’s team published their results July 30 in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.