Bite marks on a 1,800-year-old skeleton from Roman Britain suggest that a gladiator was mauled to death by a large cat, possibly a lion, a new study reports.

However, scholars who were not involved with the research had mixed responses to the team’s findings, with one expert saying that this person would not have been a gladiator and wondered if the individual was instead a condemned prisoner.

Despite the disagreement, a few things are certain: The man’s bones reveal that he was decapitated, possibly when he was dying or already dead. “The decapitation of this individual was likely either to put him out of his misery at the point of death, or for the sake of conforming to customary practice,” the authors wrote in the new study, which was published Wednesday (April 23) in the journal PLOS One.

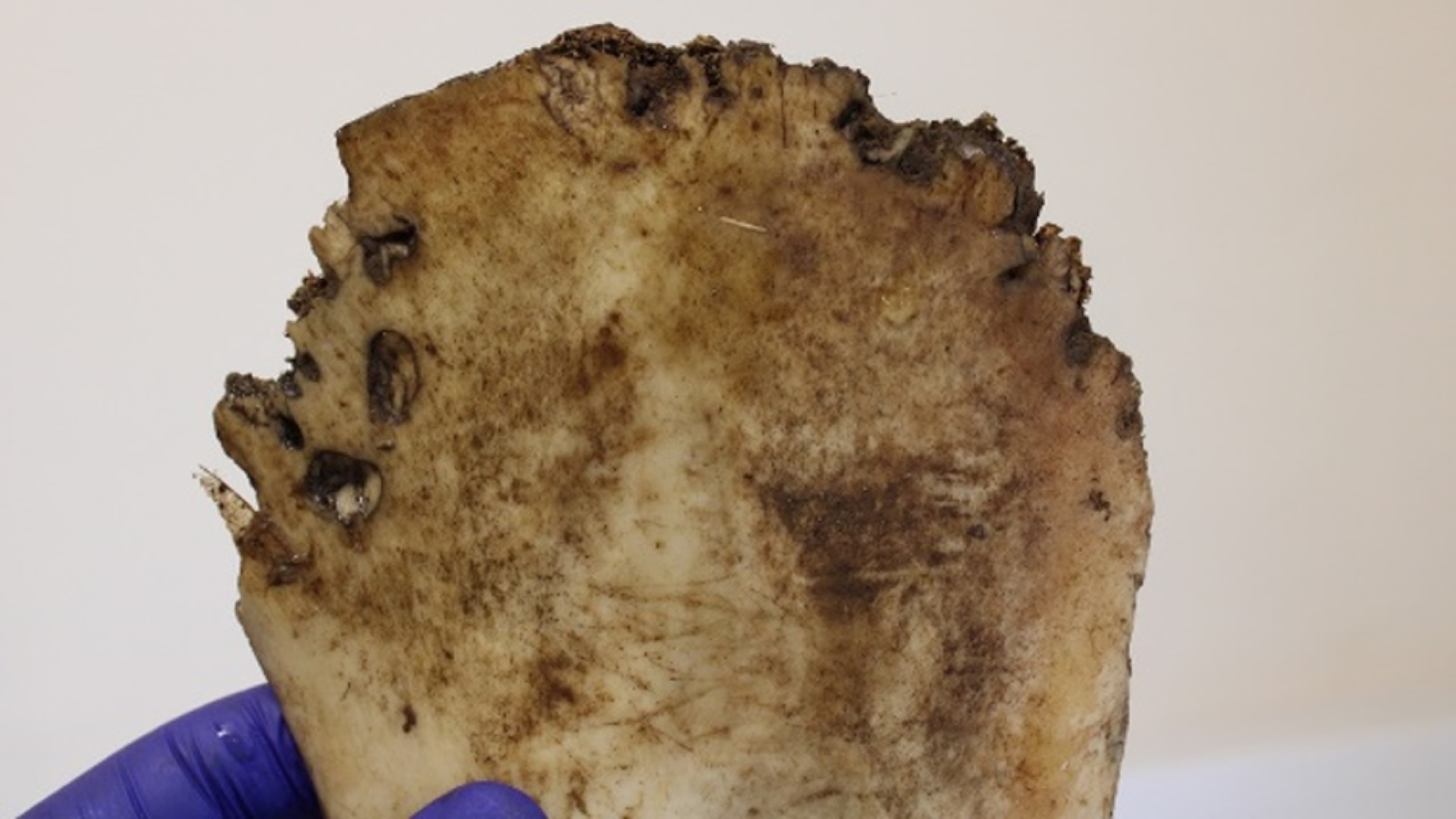

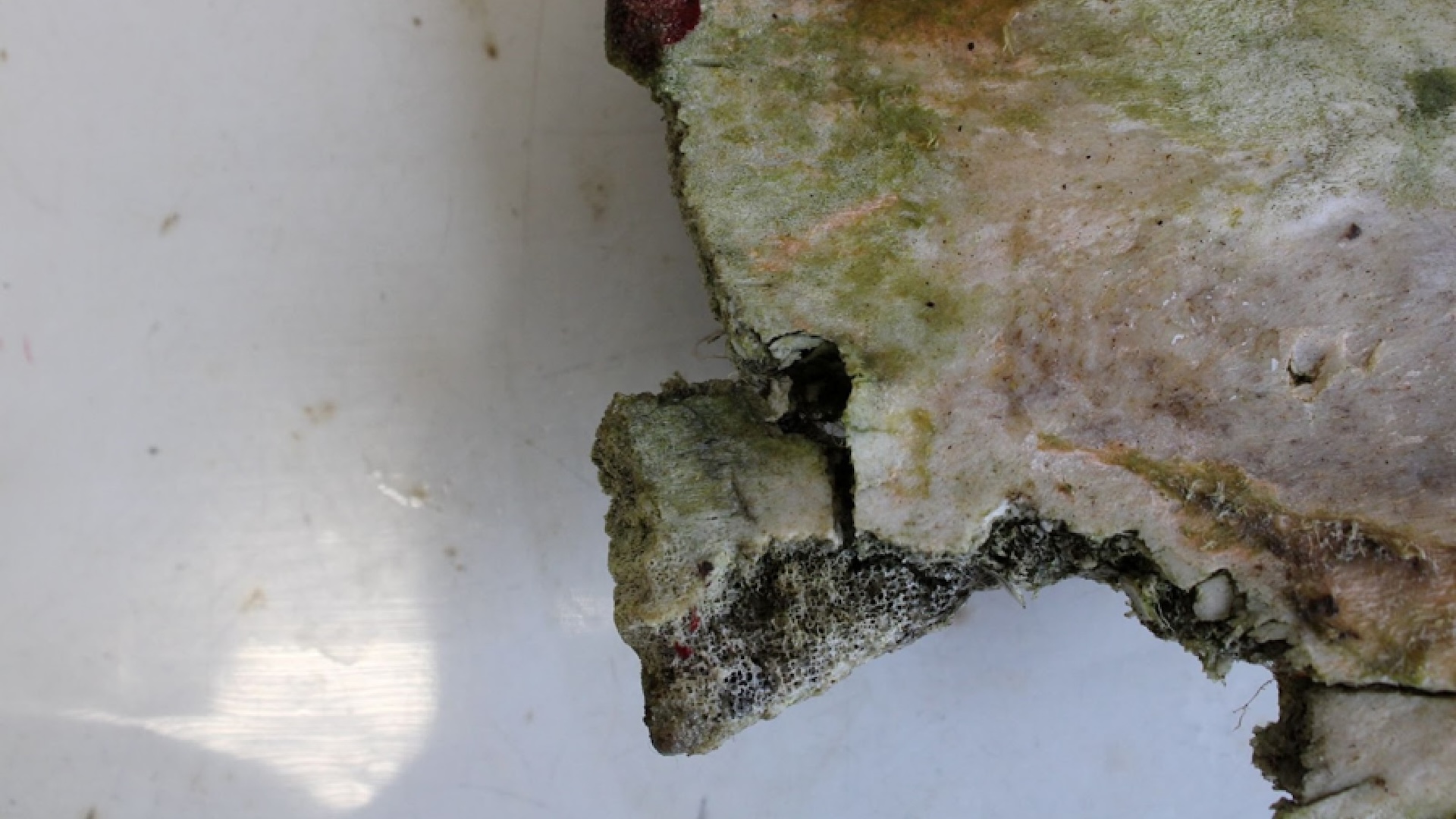

The shape and depth of the bite marks found on the man’s skeleton indicate that a large cat, possibly a lion, had mauled him. “The shape is entirely consistent with documented cases of large cat bite,” the team wrote in the paper.

The man, who was between 26 and 35 years old at the time of his death, was buried in a cemetery that is thought to contain the burials of other gladiators. In Roman times, the cemetery was in Eboracum, which is now the modern-day city of York, England.

Related: Did Roman gladiators really fight to the death?

The individual, who was excavated in 2004 and 2005, has two possible identities, said study co-author John Pearce, a reader in archaeology at King’s College London: a trained gladiator who fought the large cat with a weapon, or a man who had been condemned to death and had fought bare-handed or while tied to a post.

Pearce thinks the likeliest scenario is that the man was a trained gladiator. “The likelihood of this is high in this case because of the argument that the cemetery in which he is buried is one for gladiators,” Pearce told Live Science in an email.

The other skeletons unearthed at the cemetery have injuries consistent with those of gladiators. “There is evidence of healed trauma in the collection of bodies recovered from this site which suggests repeated fighting,” study first author Timothy Thompson, vice president for students and learning at Maynooth University in Ireland, who has a background in forensic anthropology, told Live Science in an email. Moreover, many of the buried individuals were beheaded, which sometimes happened to defeated gladiators at the end of a fight, the team wrote in the paper.

The fight in which the man died likely would have taken place in an amphitheater in the city. “As a major city in Britain and the home of a legion, Roman York would almost certainly have had at least one amphitheatre,” Pearce said. However, the amphitheater’s exact location is unclear.

Although images of fights against beasts have been found at Roman sites and textual accounts mention these battles, there has been little anthropological evidence of them until now. This is “the first physical evidence for human-animal gladiatorial combat from the Roman period seen anywhere in Europe,” the team wrote in the paper.

Long trip for a cat

The large cat would have been brought to York through a combination of sea, river and road travel, Pearce said, noting that there was “no native big cat fauna” in England. The large cat may have been brought all the way from North Africa.

“The cat would have been brought via the well-established supply routes that linked York,” Pearce said. He noted that the rivers of continental Europe, such as the Rhine and Rhone, may have been used to move the cat. The animal would have been caged or in a crate during this journey, and it would have been difficult for its handlers to have kept it fed without getting mauled. It’s not clear if the animal’s handlers had some form of tranquilizer they could use.

There would have been a high risk of the animal dying due to the stress of the lengthy journey, Pearce noted.

Controversial conclusions

Scholars who weren’t involved with the research had mixed reactions to the team’s findings.

Alfonso Mañas, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley who has studied gladiators extensively, was doubtful about many of the team’s findings. For instance, this man could not have been a gladiator, Mañas said, because in the Roman Empire, people who fought beasts were either condemned prisoners or venatores, fighters trained to fight beasts — neither of whom were considered gladiators. Gladiator researchers are “trying to eliminate the old mistake that gladiators fought beasts,” Mañas told Live Science.

He also noted that the tooth marks could have come from wolves, which are indigenous to Britain, rather than from a lion or other large cat. One possibility is that this man was executed through beheading and was bitten by a wolf or dog afterward, Mañas said.

Other researchers thought the findings presented in the article were plausible. The conclusions are “certainly an interesting and exciting prospect,” Jordon Houston, an honorary academic in the Department of Classical Studies and Ancient History at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, told Live Science in an email. “Overall, this is a great article and very well researched.”

Mike Bishop, an independent scholar who has extensively studied Roman gladiators and the Roman military, told Live Science in an email that “the paper is certainly interesting, largely for confirming what was already suspected — that human/large animal combat occurred in the north-western provinces of the empire.”

Michael Carter, a professor of classics and archaeology at Brock University in Canada who has studied gladiators extensively, was generally supportive of the paper’s findings. The team’s analysis is “convincing, and justifies the speculation that the person was killed by a large cat,” Carter told Live Science in an email. “The scenario that I imagine is most likely is that the victim had been condemned to the beasts.”