Researchers have discovered the cause of a mysterious marine epidemic that has turned billions of sea stars into goo along the West Coast — and it’s not what they expected.

Sea star wasting disease has been killing sea stars since 2013, causing catastrophic damage to ecosystems and driving the largest sea star species to the brink of extinction. Researchers thought a virus might be responsible for the disease, but after a four-year-long investigation, they’ve found that a strain of bacteria is to blame.

The pathogenic bacteria is Vibrio pectenicida, which is part of the same genus that causes cholera (V. cholerae) and produces strains that have devastated coral and shellfish populations, researchers said in a statement.

The researchers, who published their findings Monday (Aug. 4) in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, used DNA sequencing to identify microbes in infected sea stars that weren’t in healthy individuals. Eventually, the team zeroed in on high levels of V. pectenicida in infected sea star “blood,” known as coelomic fluid.

“When we looked at the coelomic fluid between exposed and healthy sea stars, there was basically one thing different: Vibrio,” senior study author Alyssa Gehman, a marine disease ecologist at the Hakai Institute and the University of British Columbia (UBC), said in the statement. “We all had chills. We thought, That’s it. We have it. That’s what causes wasting.”

Related: ‘A disembodied head walking about the sea floor on its lips’: Scientists finally work out what a starfish is

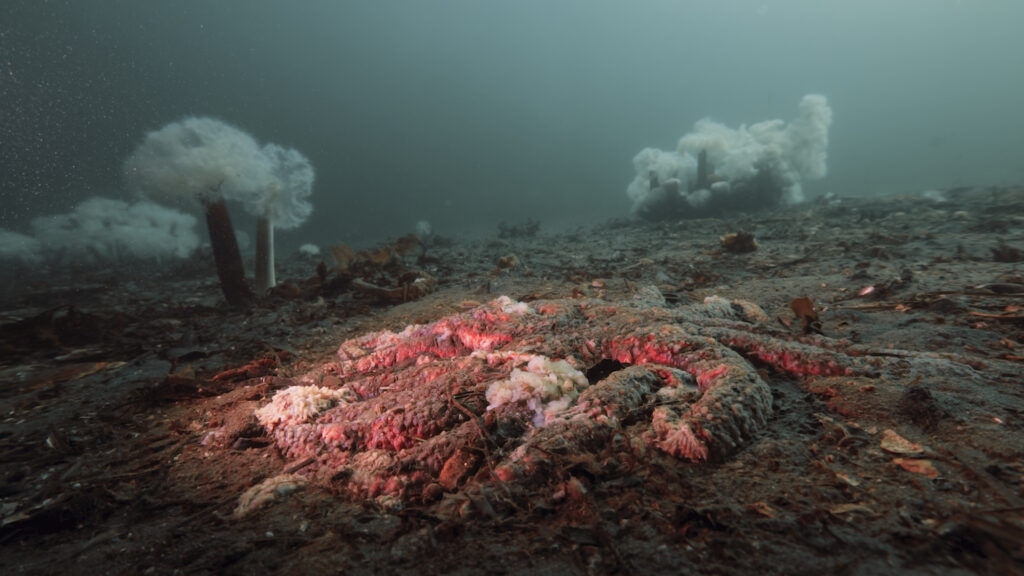

Sea star wasting disease has infected more than 20 different species, but it is particularly devastating for sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides). These giant sea stars, which can grow up to 39 inches (1 meter) in diameter, are now functionally extinct in much of their southern range in the continental U.S., while further north, they’ve suffered population losses of more than 87%. This decline has had disastrous consequences for the ecosystems they inhabit, according to the study.

Sunflower sea stars are predators that naturally keep sea urchins under control, which in turn stops the urchins from eating too much kelp. But with the sea stars sustaining heavy losses, scientists have seen urchin populations explode, leading to a major decline in kelp forests. That’s a big problem because kelp forests provide habitat for thousands of species, support local economies through fishing and tourism, are important for coastal First Nations and tribal communities, protect coastlines from storms and store carbon dioxide, according to the statement.

“When we lose billions of sea stars, that really shifts the ecological dynamics,” study first author Melanie Prentice, an evolutionary ecologist at the Hakai Institute and UBC, said in the statement. “Losing a sea star goes far beyond the loss of that single species.”

Studying wasting disease

Scientists have had a hard time finding the cause of wasting disease. The disease starts as lesions on the sea star’s body and then essentially melts tissues over the course of about two weeks, eventually reducing sea star bodies to goo. However, sea stars can present similar symptoms to other environmental stressors and diseases, making it difficult to figure out what’s behind a specific ailment. The study authors investigated lots of pathogens that they thought could have been responsible for wasting disease, before identifying the strain of V. pectenicida, known as FHCF-3.

Once the researchers had identified the strain, they created cultures of V. pectenicida from infected sea stars and gave them to healthy sea stars. The result was death for almost all of the infected sea stars, indicating that FHCF-3 was to blame for the wasting disease, according to the study. The researchers still have a lot to learn about the disease, but they can now move on to investigating its drivers and how to best fight it.

“Understanding what led to the loss of the sunflower sea star is a key step in recovering this species and all the benefits that kelp forest ecosystems provide,” Jono Wilson, the director of ocean science at the California chapter of The Nature Conservancy, which was involved in the study, said in the statement.