What if the first Martian rock samples ever deliberately hauled back to Earth landed not in Houston, but in Beijing?

That scenario, once far-fetched, is edging closer to reality. The U.S.-led Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission — long flagged as a top priority in planetary science and designed as the capstone to the Perseverance rover’s carefully-curated cache of geological samples scooped from Mars’ Jezero Crater — has stalled.

At the same time, China’s Tianwen-3 mission, designed as a leaner effort aiming to collect fewer, less carefully chosen samples, is on track for launch in 2028 with a planned return to Earth in 2031. If successful, Beijing would secure one of the most coveted prizes in planetary science years, if not decades, ahead of NASA. With China’s launch window fast approaching, experts say NASA may have already lost its chance to pull ahead.

“I don’t think it’s a competition anyway, because we already know enough about MSR’s problems and their budget issues,” Chris Impey, an astronomer at the University of Arizona who is not directly involved with either country’s sample return program, told Live Science. NASA’s mission is already far enough along, with samples cached on Mars and major hardware designed or built, that a pivot now to a nimbler, cheaper alternative that still meets the original mission timeframe is “simply not possible,” he said. “They’re stuck with the plan they have.”

The scientific payoff is immense. Returning Martian samples would allow laboratories on Earth to conduct analyses that are impossible with rover-based instruments, such as probing rocks at atomic and molecular scales, searching for organic compounds, and even scanning for fossilized microbes.

Such work could finally prove whether Mars once hosted life — or confirm that it has always been barren. Either result would revolutionize planetary science. But as with so many firsts in space, science is only part of the story.

“There is undoubtedly a certain degree of geopolitical value in being first, and the value in that regard comes from the public perception of being first or not,” Gerard van Belle, the director of science at Lowell Observatory in Arizona who is not directly involved in either country’s sample return mission, told Live Science. “The idea that maybe one mission will be better in terms of its results will probably get lost in the mix — and that’s a pity.”

Can NASA catch up?

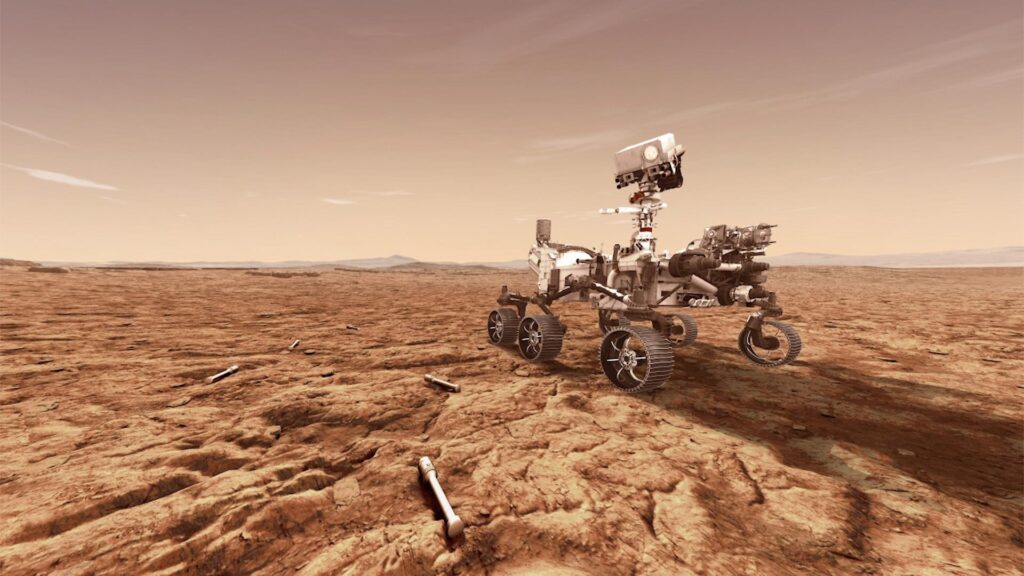

Since 2020, NASA’s Perseverance rover has been drilling and caching dozens of samples in Jezero Crater, an ancient lake bed where it recently uncovered what the agency has called the “clearest sign of life we’ve ever found on Mars.” Such carefully curated rocks, scientists argue, represent humanity’s best chance yet to determine whether the Red Planet was ever home to life.

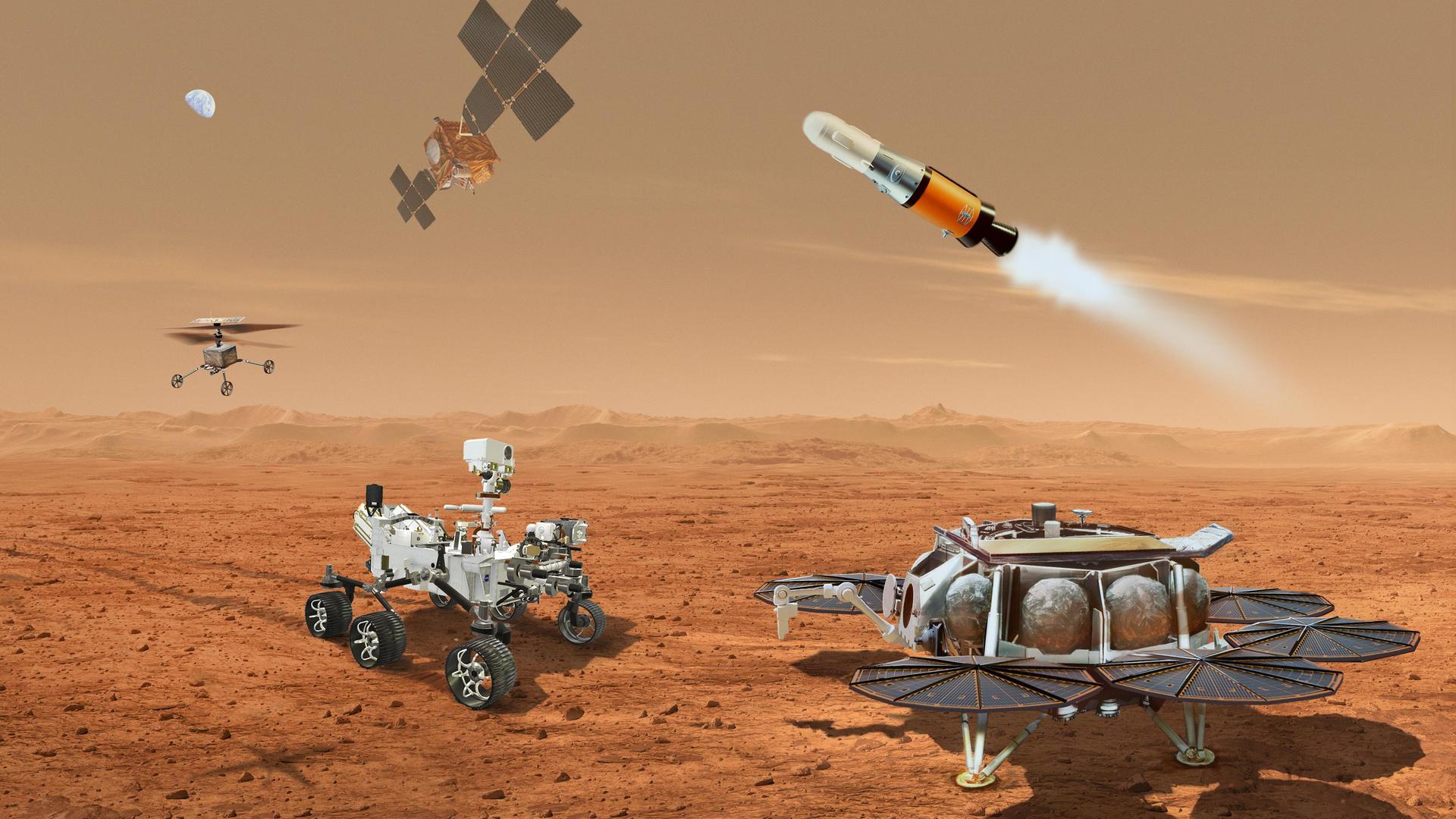

But getting them home is proving elusive. The U.S.-led MSR, a joint project with the European Space Agency, was conceived as a high-stakes chain of complex handoffs: Perseverance’s cache would be fetched by a lander, transferred by robotic arm into a Mars Ascent Vehicle, and then launched into orbit for capture by a return spacecraft.

Even after plans for a “fetch rover” were later dropped in favor of a pair of miniature helicopters, the choreography remained astronomically expensive. With costs swelling past $11 billion and timelines sliding toward 2040, NASA declared the plan untenable in 2024.

“Maybe if the U.S. had to rethink it, they might have cast a slightly different path, where they might have gone with a simpler mission first — maybe,” said van Belle.

Earlier this year, NASA outlined two scaled-back alternatives. Either would require an immediate $300 million commitment from Congress to stay on track, with a launch around 2030 and the return of about 30 Martian samples between 2035 and 2039.

Even so, Impey doubts NASA can regain lost ground. “I don’t think they can accelerate the timeline, even if they got the money they are asking for currently,” he said.

China’s Tianwen-3, by contrast, is betting on a self-contained mission whose playbook was proven effective by its recent moon missions, which returned lunar samples with Chang’e-5 in 2020 and Chang’e-6 in 2024 — the latter gathering the first samples ever scooped from the moon’s unexplored far side.

Tianwen-3 calls for two launches: one carrying a lander equipped with a drill, robotic arm and helicopter scout, and the other carrying an orbiter-returner spacecraft. Using a “grab-and-go” approach, the lander would collect samples and load them directly into its ascent vehicle. After about two months on the surface, that rocket-powered stage would launch to meet the orbiter-returner in Mars orbit, which would then ferry about 1 pound (500 grams) of material back to Earth.

The Chinese mission plans to target a flatter, less geologically diverse landing site than Jezero, chosen for safety rather than scientific promise. That means the samples may be less revealing than Perseverance’s cache. Still, Tianwen-3 is more likely to stay on schedule, as it is embedded in China’s long-term space strategy — one that is healthily funded and has already returned lunar samples, built a space station, and set goals for a permanent moon base by 2035 and crewed missions to Mars by 2050.

“[China’s] timelines are a few decades, but the timelines for NASA are almost dissolving as we watch,” Impey said. “So, if there is a space race, China’s already winning it, and could win it dramatically in the next few decades.”

A new Sputnik moment?

NASA’s obstacles are not purely technical. The White House has proposed steep cuts — nearly halving NASA’s science budget and slashing its overall funding by 24%, from $24.8 billion to $18.8 billion. If enacted, it would mark the steepest single-year cut in NASA’s history, even deeper than the reductions after the Apollo program wound down in the 1970s.

The coming fiscal year will be decisive, Impey said. If the cuts are enacted, they will not only jeopardize MSR but also trigger broader reductions across active observatories and planetary probes.

“That would be devastating,” said Impey. “That’s a cliff that they could fall off — and if they fall off that cliff, then the U.S.-led MSR effort is certainly not going to happen for decades.”

If China returns Mars samples first, the symbolism would potentially echo a new Sputnik moment. In 1957, the Soviet Union’s launch of the first artificial satellite stunned the U.S., spurred the creation of NASA, drove massive investment in science and engineering education, and ultimately accelerated the space race that culminated in the Apollo moon landings a decade later.

Planetary scientists eager to know about Mars’ past habitability emphasize that they want to see the U.S.-led Mars Sample Return mission succeed, even if it has to be delayed, rather than see the plug pulled entirely.

“What’s important is, can you answer the question of whether there was or is life on Mars?” said Impey.

But no single mission is guaranteed to settle that question, he cautioned. Each will return only a small cache of rocks from a single region of a vast, complex planet. That makes it all the more critical that both NASA and China succeed in their sample return plans, since together their efforts could offer complementary pieces of the puzzle.

“If you brought back the perfect rock, yes, you could get lucky,” Impey added. “There is still a chance that a single shot sample return from one location just won’t answer the question.”