Quick facts about earthquakes

Where the most earthquakes happen: The Pacific “Ring of Fire,” where many tectonic plates meet

The biggest earthquake ever recorded: A magnitude 9.5 earthquake in Chile in 1960

The deadliest earthquake: An estimated magnitude 8 quake in central China in 1556

Number of earthquakes around the world each year: Around 500,000

Earth’s crust is the planet’s outermost layer. It is made of solid rock and sits on top of another layer, called the mantle. The mantle flows and stretches like bubble gum, while the crust above it cracks like hard candy. When it does, it releases energy in a burst, which causes the shaking of an earthquake.

Earthquakes happen most often where tectonic plates meet. Tectonic plates are pieces of crust that fit together like puzzle pieces. Sometimes these plates slide alongside each other at what are called transform plate boundaries. Sometimes they pull apart at divergent boundaries, and sometimes they push together at convergent boundaries. When plates come together at convergent boundaries, they often slide under each other, which is called subduction. All of these movements can cause earthquakes. Earthquakes can build mountains or tear a continent apart. The places where pieces of crust move against each other are called fault lines, and scientists monitor fault lines to measure earthquakes. However, despite decades of trying, scientists still can’t predict exactly when or where a quake will happen.

5 fast facts about earthquakes

- The biggest earthquakes happen at “subduction zones,” the points where one tectonic plate slides under another. Big subduction zone earthquakes can release the same amount of energy as tens of thousands of atomic bombs.

- The famous San Andreas Fault in California is between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate. It is 750 miles (1,200 kilometers) long.

- Indonesia has the most earthquakes of any country, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. But the most earthquakes are recorded in Japan, where scientists have many instruments that can detect quakes too small for people to feel.

- The most earthquake-prone U.S. state is Alaska.

- Humans can cause earthquakes. Some oil and gas drilling companies inject large amounts of water underground, and this water can make faults slip, triggering quakes in places like Oklahoma and Texas.

Everything you need to know about earthquakes

What causes earthquakes?

Most earthquakes are caused by the movements of tectonic plates. Sometimes, tectonic plates move very slowly — at the rate your fingernails grow — without causing the ground to shake. But sometimes, they get stuck against one another. Stress builds up until the pressure is too great, and then the plates move all at once, releasing tons of energy.

The energy from an earthquake travels in waves. The fastest wave is called a P wave, and it shakes the earth by squeezing material as it moves through, like the coils of a Slinky being squished together. Next comes the S wave, which moves up and down like a wave. Both types of waves shake the ground.

How much shaking you feel depends on the size of the earthquake, but it also depends on the type of ground you’re on. Soft ground shakes more than hard ground, and wet soil can sometimes liquefy, or act like a liquid, during an earthquake. Liquefaction can cause buildings to sink several feet into the ground.

Where do earthquakes happen?

About 90% of earthquakes happen along the Pacific Ring of Fire, which stretches all the way from New Zealand, up through Indonesia and Japan, across the Pacific at Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, and down the west coast of North, Central and South America. The Ring of Fire exists where the Pacific Plate, which sits under the ocean, meets with many other tectonic plates.

The Ring of Fire is where most of Earth’s really big earthquakes happen. For instance, the largest earthquake ever recorded on Earth occurred on the Ring of Fire: The Valdivia earthquake, which struck Chile on May 22, 1960. Seismic monitoring wasn’t as widespread back then, but scientists estimate this devastating quake had a magnitude of 9.5. The largest earthquake to hit the United States was a magnitude 9.2 quake that was also on the Ring of Fire. It shook Prince William Sound, Alaska, on March 27, 1964.

There are two other “earthquake belts” where most of the rest of the earthquakes on the planet happen. One is the Alpide earthquake belt, which starts in Indonesia and stretches west all the way through the Himalayas and Mediterranean and into the Atlantic Ocean. The other is the mid-Atlantic ridge. Luckily, the mid-Atlantic ridge is deep under the ocean, so earthquakes that occur there don’t affect very many people. The exception isIceland, which is known for its volcanoes and hot springs. The country sits on this earthquake belt and experiences both quakes and volcanic eruptions.

Can earthquakes be predicted?

We know which areas are likely to have lots of earthquakes, and scientists can even identify faults where large quakes have happened in the past and might happen again. But there is no way to predict exactly when or where an earthquake will start.

Sometimes there will be some small earthquakes, called foreshocks, before an even bigger earthquake, called the mainshock. But scientists can’t tell beforehand whether a quake is a foreshock or a mainshock. Some stories suggest that some animals might act oddly before an earthquake, but those stories are scattered and inconsistent. Most of the time, people don’t have good records of how an animal behaves before, during, and after a quake, so it’s hard to draw any conclusions about whether the behavior was really out of the ordinary. One study suggested that animals might be able to feel foreshocks that most humans don’t notice, however.

Although scientists can’t predict earthquakes, they can predict earthquake shaking a tiny bit in advance for people living near the quake epicenter (the place where the earthquake starts). Earthquake waves take time to travel, so in places with lots of monitoring stations, like Japan, an automatic system can detect the first shaking and send text messages to people farther away. This can give people a few seconds of warning to “drop, cover, and hold on.” Automatic earthquake detection can also slow down trains, turn off water valves, and do other things to protect buildings and equipment from damage.

How are earthquakes measured?

Earthquakes are measured with devices called seismographs, which are made of two parts: a base that sticks firmly to the ground, and a weight on a spring that can move freely. When a quake happens, the weight’s movement records how much the ground moves.

Networks of seismographs all around the world are constantly working to record ground motion. Some use GPS, like the navigation system on a smartphone, to precisely measure how much the ground is moving — even when a fault is creeping along so slowly that it doesn’t create shaking.

Scientists translate seismograph measurements into an earthquake’s magnitude, which describes the quake’s size. Quakes with magnitudes less than about 2.5 usually can’t be felt. Quakes between 2.5 and 5.4 are minor and typically cause little damage. For every whole number increase on the scale — from 1 to 2 or 2 to 3, for example — the earthquake releases 32 times more energy. There is no top end of the scale, but scientists say a magnitude 10 is unlikely.

How much shaking an earthquake causes can depend on a lot of factors, including how far you are from the epicenter and how firm the ground is. Scientists in the U.S. measure an earthquake’s intensity on another scale, called the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. This scale describes how strong the shaking feels and how much damage it does to buildings of different types and building quality. The Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale goes from 1 to 10 but uses Roman numerals. A “II,” or 2, is weak shaking, while an “X,” or 10, is extreme shaking that destroys well-built structures.

How do we prepare for earthquakes?

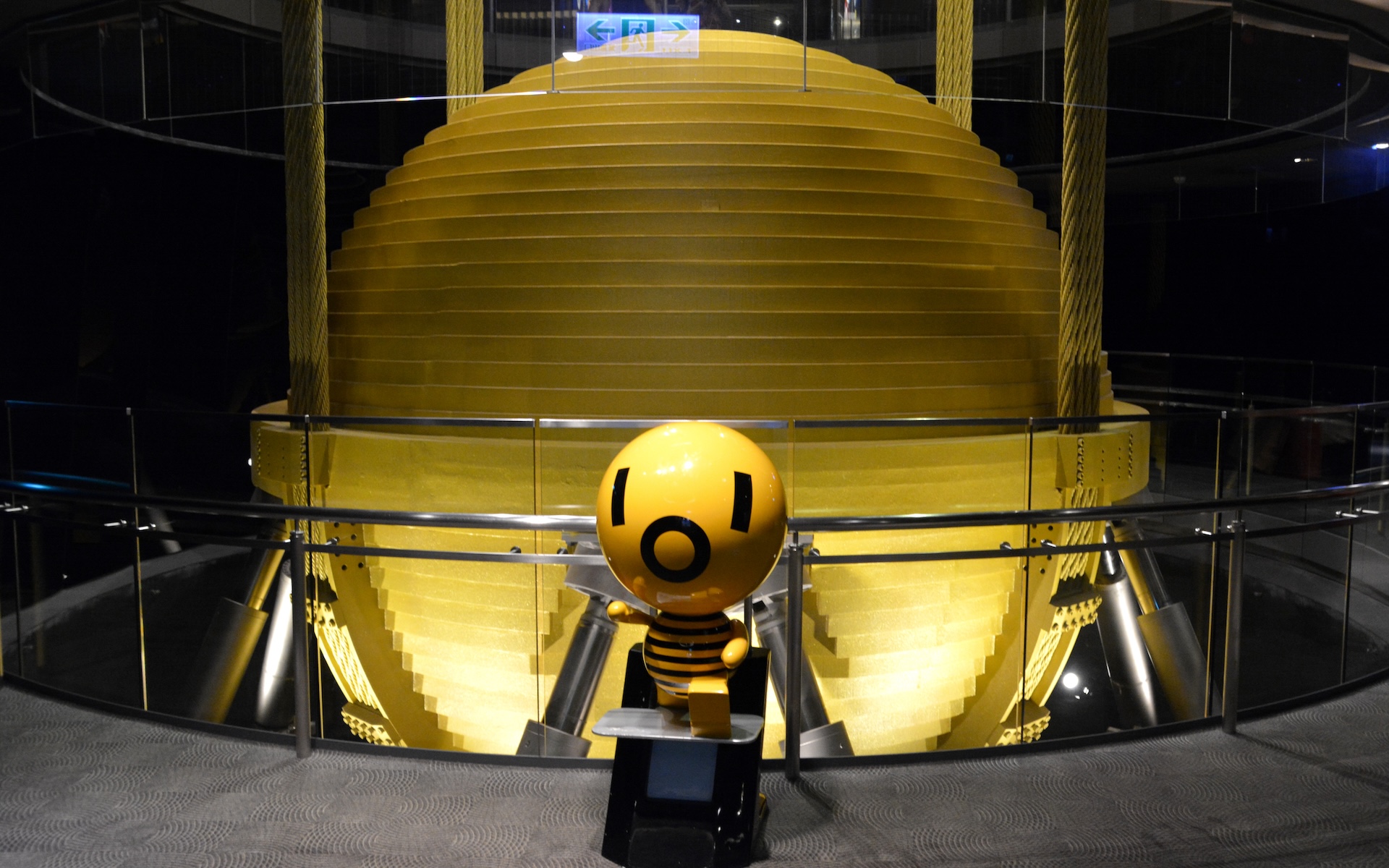

One of the biggest risks during an earthquake is building collapse. Poorly built structures are at risk, but even well-built structures that are not designed to withstand earthquake shaking can be dangerous too. For example, bricks are generally sturdy, but buildings made of bricks are very prone to falling apart when they experience earthquake shaking. Reinforcing brick buildings with steel rods helps keep them from collapsing during earthquakes. Skyscrapers in quake-prone places, like Chile and Japan, are built to absorb energy. They have reinforced steel skeletons, which sway with a quake rather than collapsing, their foundations are often set on rubber pads, and they have liquid-filled “dampers” built into their structure that soften the impact of earthquake waves.

Some of these dampers are really big and impressive. Taipei 101, a 101-story skyscraper in Taiwan’s capital city, is protected by a swaying, golden ball suspended within an upper floor that is 18 feet in diameter — as wide as a giraffe is tall. The skinniest skyscraper in the world, the Steinway Tower in New York City, has a mass damper in its frame that weighs 800 tons — about as heavy as four blue whales.

People in earthquake-prone areas also take precautions by hanging only light objects on walls and not placing shelves over places where people often sit or sleep. When an earthquake begins, experts recommend you “stop, drop, and cover.” Stop where you are, and drop the floor so you don’t get knocked down. Cover your head and neck with a free arm. If a desk or sturdy table is nearby, crawl underneath it. Otherwise, crawl next to an interior wall and remain crouched, protecting the middle of your body. Then, hold on until the shaking stops. Experts give this advice because falling debris and breaking window glass can be major causes of injuries in earthquakes.

Fire can be another big risk after an earthquake, because pipes that carry gas into buildings may break and release flammable vapors. Engineers make buildings safer by making gas lines out of flexible materials in earthquake country. They can also brace equipment so it moves less in an earthquake and install automatic shutoff valves that close off the flow of gas when the ground starts to shake.

When earthquakes occur under the ocean, they can sometimes trigger tsunamis. Coastal areas have tsunami warning systems that tell people to head to high ground if a tsunami is possible.

Earthquake pictures

Discover more about earthquakes

—Earthquake risk in California (California Earthquake Authority)